On this page

- Community-driven alternative commissioning approaches can strengthen the community-controlled disability sector

- Box 2 Initiatives to improve First Nations participant experience

- Place-based and community-driven alternative commissioning approaches can generate more responsive and sustainable supply in remote areas

- Finding 2 Alternative commissioning approaches for both First Nations and remote communities

Evidence from past and ongoing reviews and inquiries[17] continues to show that the current market-based model with individualised funding arrangements persistently fail to meet the needs of both First Nations and remote communities.

Whilst there are thin markets and gaps in available disability services and supports in all locations that are culturally inclusive and safe, there are additional thin market challenges in rural, remote, very remote locations. For example, cost, existence of community-controlled organisations already delivering a range of services with different reporting, regulatory and governance requirements, workforce, and appropriate infrastructure. This exists for both NDIS and non-NDIS related service delivery.

The NDIS has gone some way to improving equity in access to supports for First Nations people with disability. As at 31 December 2022, 7.4% of NDIS participants identify as First Nations participants[19]. Over 60% of First Nations participants in remote and very remote communities are receiving disability supports for the first time[20].

However, First Nations participants and participants living in remote communities still face persistent challenges in accessing NDIS supports. Broader systemic issues around the participant experience with the NDIS are exacerbated.

We have received inconsistent advice on whether ‘return to country’ for short visits to connect with family, or participate in ceremony, is funded under the NDIS as some planners have considered those visits as a holiday rather than a cultural, necessary and reasonable support requirement.

Improving outcomes for First Nations participants require accessible, culturally appropriate NDIS supports that take into account the strengths of First Nations communities.

A historic lack of services within remote communities pre-dates the NDIS and has led to limited or no knowledge and understanding of disability supports[22]. In remote communities, the increased demand for services - which has been driven by the NDIS – has often not been met with an increase in services[23].

Back to topCommunity-driven alternative commissioning approaches can strengthen the community-controlled disability sector

Complex NDIS policies and processes have made it difficult for First Nations people with disability to access and navigate the NDIS. The relatively low number of First Nations participants with a plan and the cultural appropriateness of planning processes were among the many concerns raised during the 2020 Joint Standing Committee Inquiry into NDIS Planning.

Compared to non-Indigenous participants, First Nations participants have higher value plans. Lower levels of plan utilisation arise from lower levels of spending[24]

Limited availability of accessible, culturally appropriate care and supports (Figure 8) may mean First Nations participants need to choose between getting culturally unsafe supports, and not getting funded supports at all.

Aboriginal people will only access those services where they feel culturally safe and prefer to use Aboriginal community-controlled health services when available.

First Nations community-controlled organisations may be reluctant to deliver NDIS services. Individualised funding packages can provide uncertain funding for community-controlled organisations, limiting their ability to build trust within the communities they are supporting. This uncertain can also limit their ability to invest in longer term staffing contracts.

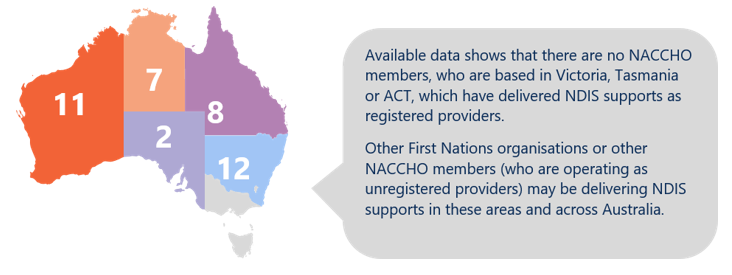

Note: Data only includes organisations who are members of the NACCHO, are registered NDIS providers, and have previously delivered and claimed supports against an NDIS participant’s plan as at 31 December 2022.

Source: NDIA data, December 2022 (unpublished)[26]

The capacity of First Nations communities – which include First Nations people with disability, their family and kin, community, and provider organisations – to drive and develop culturally appropriate care and supports is also being hindered in the current approach (Figure 9).

A number of ongoing initiatives are aimed at ensuring the NDIS is more culturally safe and responsive for First Nations people to access and navigate the NDIS (Box 2).

Building the cultural competency of existing NDIS providers will go some way to strengthening the responsiveness, quality, and range of services delivered to First Nations people with disability[28].

Priority should be to strengthen the community-controlled disability sector. Building the First Nations community-controlled sectors is one of four Priority Reform areas under the 2019 National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the Closing the Gap National Agreement). The disability sector is one of four initial sectors identified for joint national strengthening effort.

As part of this, the 2022 Disability Sector Strengthening Plan (DSSP) outlines six key areas for action to build the capacity of existing and new community-controlled disability services to deliver a full range of culturally safe and inclusive services. Key actions include localised community-led strategies, joined up service delivery and strengthening a dedicated First Nations disability workforce that embeds a cultural model of inclusion.

Investment in strengthening community-controlled disability services for all First Nations people with disability is also a priority for First Nations disability sector stakeholders.

First Peoples with Disability Network’s “National Disability Footprint” and “Ten priorities to address disability inequity” are both underpinned by building the capacity of First Nations’ community-controlled organisations and growing the First Nations disability workforce.

Using alternative commissioning approaches, First Nations communities could commission community-controlled organisations to ensure the availability of disability supports that are responsive to their needs, particularly where the market has failed to respond.

In this way, community-driven alternative commissioning approaches can be a powerful tool to deliver culturally appropriate supports across metropolitan, rural and remote Australia.

Back to topPlace-based and community-driven alternative commissioning approaches can generate more responsive and sustainable supply in remote areas

Challenges in delivering services to remote areas are well-known. These are not unique to the NDIS, but they are amplified by the current market-based model with individualised funding arrangements.

- Demand is often low, geographically dispersed and fragmented across government and non-government systems in remote areas[31].

- Individualised funding arrangements further fragments an already low, dispersed demand for services. They also increase demand risk – where actual demand for services is lower than the forecasted demand – since service providers are more exposed to changes in demand when a participant’s NDIS funding is reassessed[32].

- Service delivery costs are inherently higher in remote and very remote Australia[33]. These costs – such as investment for capital infrastructure and travel for fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) and drive-in, drive-out (DIDO) arrangements – particularly impact providers’ financial viability since, under a market-based approach, these costs are often not shared across service providers[34].

- Service providers also face more pronounced logistical difficulties and more acute workforce challenges in delivering services to remote and very remote Australia[35].

- Prospective local providers are reluctant to register as NDIS providers due to the regulatory impost and cost[36]. Existing First Nations community-controlled organisations are also reluctant to deliver NDIS services due to the financial risks involved and potential reputational risk with the broader community[37].

No one-size-fits-all approach to delivering NDIS supports will work for remote communities.

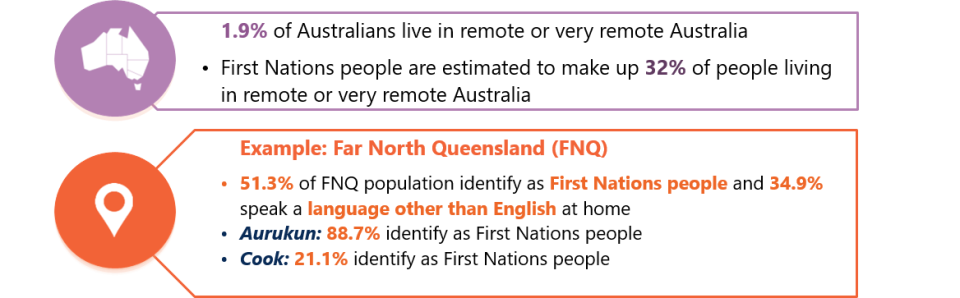

Each remote community has unique geographical considerations, demographic compositions and cultural contexts (Figure 10). For First Nations communities, connection to land, community, culture and kin also cannot be underestimated, particularly in remote Australia.

Social and emotional wellbeing is the foundation of physical and mental health for Indigenous Australians. It is a holistic concept that encompasses the importance of connection to land, culture, spirituality and ancestry, and how these affect the wellbeing of the individual and the community.

Note: Far North Queensland (Statistical Area Level 3) covers 16 local government areas (LGA).

Pricing initiatives to date go some way in addressing these challenges …

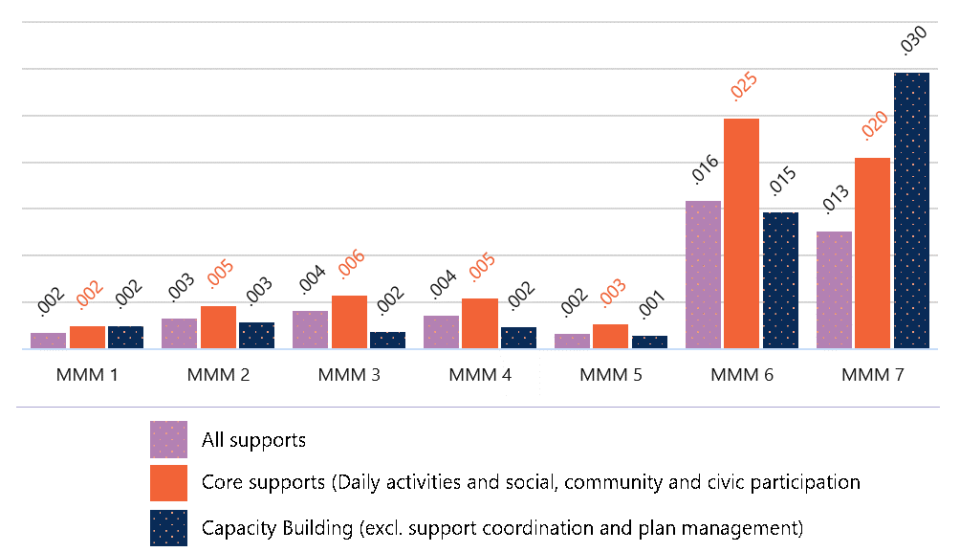

Price limits for NDIS supports have been adjusted in recognition of the costs associated with delivering supports to remote areas[40].

In July 2019, remote and very remote loadings have been uniformly increased from 20% and 25% to 40% and 50% respectively[41]. From 2020 onwards, the NDIA also introduced more flexible pricing arrangements allowing for services to be delivered via other models, including via telehealth.

This has seen some improvements in access to supports. Average NDIS plan utilisation rates increased slightly in remote areas – from 63% in June 2019 to 68% in December 2022. Very remote areas have seen a larger change – increasing from 39% in June 2019 to 52% in December 2022.

Even so, participant outcomes in remote and very remote communities still lag well behind metropolitan and regional areas, which had average plan utilisation rates of over 70% in December 2021 (Figure 11).

| Price of an hour of standard care | Price June 2019 | Price Dec 2021 | Nominal increases in price, including loading (%) | Utilisation June 2019 | Utilisation December 2022 | Increase in utilisation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMM 1 | $45.54 | $57.23 | 25.7% | 69% | 76% | 7% |

| MMM 2 | $45.54 | $57.23 | 25.7% | 69% | 74% | 5% |

| MMM 3 | $45.54 | $57.23 | 25.7% | 67% | 71% | 4% |

| MMM 4 | $45.54 | $57.23 | 25.7% | 65% | 66% | 1% |

| MMM 5 | $45.54 | $57.23 | 25.7% | 58% | 68% | 10% |

| MMM 6 | $54.65 | $80.12 | 46.6% | 63% | 68% | 5% |

| MMM 7 | $56.93 | $85.85 | 50.8% | 39% | 52% | 13% |

… but market gaps persist in remote and very remote communities

Applying a market-based approach to deliver high quality supports to, and outcomes for, NDIS participants in remote and very remote communities is not working.

Persistent market gaps remain through many remote and very remote communities. In December 2022, recorded market gaps were around 14% for remote participants and 27% for very remote participants. This means that utilisation of supports by remote and very remote participants is 14% and 27% lower compared with median utilisation rate for participants in the scheme for over two years receiving face-to-face supports from registered providers.[43]

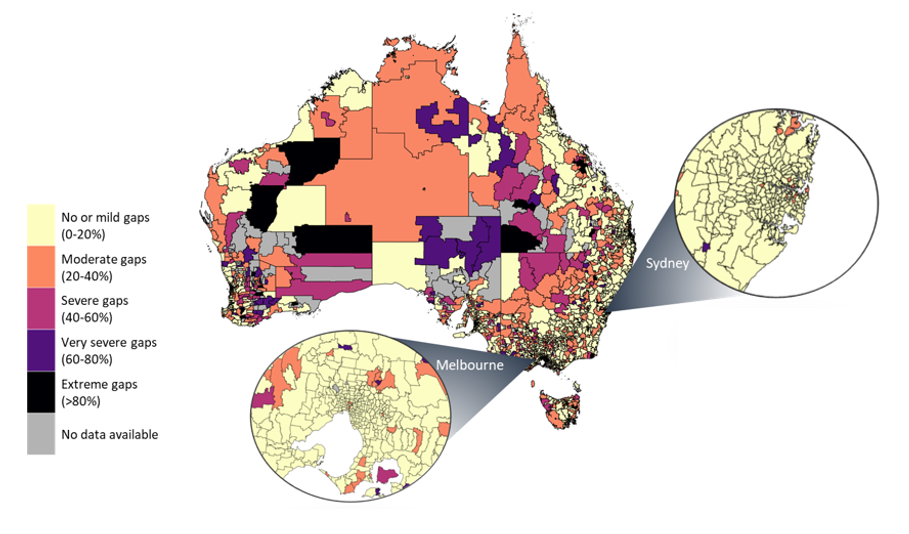

These averages also conceal the severity of market gaps across remote Australia, with a number of locations experiencing market gaps of over 40% in 2022 (Figure 12).

In remote and very remote areas, the severity of market gaps may mean some participants could be trading off their ability to remain in their community against their access to supports. Often there is a greater need for local, culturally safe supports to be delivered to First Nations participants in remote areas, but First Nations organisations can be reluctant to become NDIS providers due to the regulatory impost and reputational risks involved.

Many [First Nations] people were born in remote communities and due to their high level support needs had no other option but to relocate to urban areas to access essential supports.

Notes:

1. Market gaps were calculated for participants in the scheme for two or more years. Utilisation rates were compared for participants residing in each postcode with the national median plan utilisation.

2. Postcodes were used to calculate market gaps rather than larger Local Government Areas (LGAs) since LGAs can span multiple remoteness categories.

3. Pop-out maps showing the greater Sydney and Melbourne areas are provided as examples of market gaps in major cities.

4. This data is at 31 December 2022 and excludes in-kind supports.

Even where participants are getting services, many of these services rely heavily on FIFO and DIDO arrangements rather than local, on-the-ground solutions.

…there is a reliance on fly-in fly-out (FIFO) and drive-in drive out (DIDO) arrangements to provide services in these communities. This is very expensive, represents little value for money, and may also not be the best for the participants.

Where they are concerned about the safety and quality of available services (including cultural safety), participants often have little recourse to find safer or better quality services due to low market competition within these communities (Figure 13).

Moving to place-based and community-driven alternative commissioning approaches can offer opportunities to create more holistic and sustainable, local services and create sustainable jobs in remote communities.

Note: Market concentration by remoteness is calculated using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), and is based on registered and unregistered providers paid during 1 January to 30 September 2022. Visibility of unregistered providers depends on capture of Australian Business Numbers (ABNs) by plan managers. It excludes claims for self-managed supports.

Alternative commissioning can lower demand risk and costs for communities

In failing to deliver safe, quality and timely supports and outcomes for participants in remote communities and in First Nations communities, the current market-based model also drive poor outcomes and upward pressures on the long term costs of the NDIS for these participants.

Failing to deliver participant outcomes in these communities also puts pressure on the entire care and support ecosystem. A lack of timely supports may lead to increased hospitalisation rates or lengthier hospital stays, which in turn increases pressure on the primary healthcare system.

Alternative commissioning approaches provide opportunity to:

- Lower the cost of service delivery by offering service providers greater certainty of demand to invest in more effective service delivery models – this includes models that better coordinate and target investment in building and maintaining community infrastructure. Existing initiatives (including those by non-profit organisations, local, state or territory and Commonwealth governments) can be leveraged and built upon, while new initiatives could be better targeted where need is most pressing. More effective service delivery models could also strengthen investment in local workforce and rely less on costly and ineffective FIFO and DIDO models.

- Improve health and wellbeing outcomes for both First Nations and remote communities using a more holistic, lifetime-based approach – for example, the FNQ Connect (Case Study 2) noted ‘Improving integration of care and support will improve quality of life and health outcomes which will lead to a reduction in potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) and reduced pressure on the hospital sector over the medium‑to‑long term’.

As outlined in the Closing the Gap National Agreement, better life outcomes are also achieved when First Nations people have a genuine say in the how services are designed and delivered.

Back to top