On this page

- There are a range of alternative commissioning approaches

- Case Study 2 Far North Queensland (FNQ) Connect – a community-driven proposal for integrated care to address low and fragmented supply

- Approaches need to be underpinned by strong partnerships

- The timing of roll out should be community-led

- Recommendation 1 Working in partnership with First Nations representatives and remote communities to roll out alternative commissioning approaches

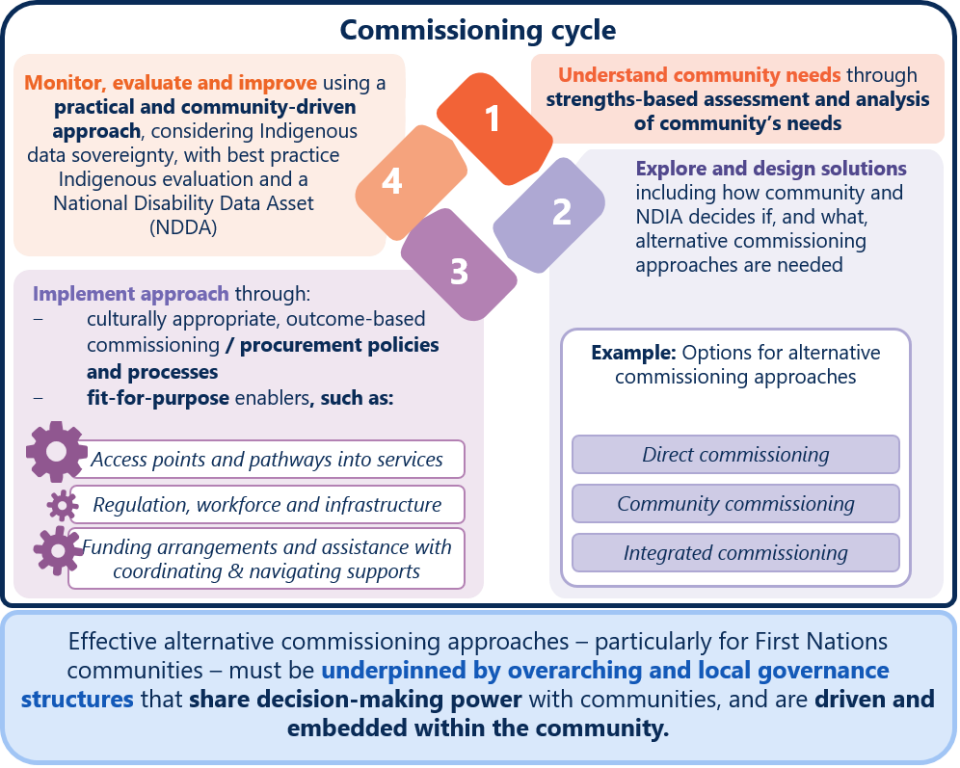

To be effective in improving service delivery for both First Nations communities and remote communities, alternative commissioning needs to follow a commissioning cycle (Figure 14). The cycle involves:

- understanding communities’ strengths and needs, including what initiatives and infrastructure already exist on the ground and can be built upon

- exploring and designing solutions from the ground up based on local needs and priorities

- implementing the approach by selecting, overseeing, and engaging with providers and managing contracts. Implementation should also consider complementary policy or ‘enablers’, including: the role of intermediary supports, regulatory settings for ensuring appropriate quality and safeguarding, and pathways to access services

- ongoing monitoring, evaluation, and improvement.

There are a range of alternative commissioning approaches

As noted above, alternative commissioning approaches are not returning to ‘block funding’. Instead, they should provide participants – particularly those living in remote and very remote areas – with better continuity of services while offering choice and control over which service delivery model best suits the needs of the local community.

Alternative commissioning approaches could be designed to coordinate demand for a number of NDIS supports within the community. Participants could flexibly access what they need, when they need. Design options could aim to set service providers up to deliver supports responsively to local needs and sustainably over the long term.

Alternative commissioning approaches could also be designed to coordinate demand for care and supports across disability supports (both funded by NDIS and other governments), health, aged care and veterans’ care supports.

Rather than separately funding different supports and community capacity building initiatives, funding for services could be more coordinated (or ‘integrated’) across programs to minimise duplication and gaps.

Services in remote Indigenous communities are often poorly planned and uncoordinated, both between and within governments, and between service providers. Decisions about service provision are made on the basis of jurisdictional, departmental and program boundaries, and this may come at the expense of a focus on outcomes for users.[48]

Integrated commissioning approaches would make it clearer and easier for communities – particularly in remote areas – to understand what services they can access, from who and when.

Having a single interface point for services such as disability support, aged care and veterans’ care supports can provide better wrap-around supports and services with smoother transitions across different life stages. For example, the Far North Queensland Connect: Connecting people, connecting care (FNQ Connect)[49] proposes developing a joint funding mechanism to align resources (Case Study 2).

For potential and existing service providers, integrated commissioning approaches may make it easier to achieve scale and reduce demand risk across the various care and supports needed in the community. Design of the enablers for alternative commissioning approaches (Figure 15) may also make it easier for service providers to deliver supports in the community by reducing the complexity in different care and support program approaches.

Communities could also drive the design and lead the commissioning process for the supports they need. Community commissioning approaches could use different commissioning approaches, such as integrated commissioning.

Back to topApproaches need to be underpinned by strong partnerships

The most critical element of this cycle is governance structures that share decision-making power with First Nations representatives and communities. This has been agreed to in the Closing the Gap National Agreement, endorsed by all jurisdictions.

Closing the Gap National Agreement

The Closing the Gap National Agreement commits all Australian governments to work in full and genuine partnership with First Nations people in making policies to close the gap.

In exploring alternative commissioning approaches with communities, governments should ensure they continue to work in partnership with First Nations people and give effect to the four Priority Reforms (Figure 15).

The NDIA is taking important steps towards building genuine partnerships with First Nations representatives and peoples (Box 2). However, it will take time for the NDIA to build these partnerships.

Strong partnerships will be necessary among communities, local First Nations organisations and experienced disability service providers. They will need to build each other’s knowledge and understanding of disability, culturally appropriate ways of doing business and the individual community context. Time will also be needed for potential providers to build capacity and capability to respond to the participants’ needs.

The Disability Sector Strengthening Plan

The DSSP also provides a framework of engaging with and responding to the needs of First Nations people with disability. All jurisdictions committed to the Guiding Principles (Figure 16) as a set of minimum standards when developing policies, programs, services and systems for First Nations Peoples with disability.

Alternative commissioning approaches aligned with DSSP action to implement localised community-led strategies to respond to NDIS thin markets. These DSSP action include investing in the community-controlled sector to design and implement place-based approaches that address thin markets across Australia. The DSSP also outlines actions to facilitate a process for community-controlled organisations to provide NDIS services.

The timing of roll out should be community-led

Expanding new approaches in remote communities too far, too fast is a significant risk[51].

Roll out should also be on a case-by-case basis, depending on each community’s capacity and capability. For example, community commissioning approaches (Figure 5) should draw on a community’s capacity at the time to lead the alternative commissioning approach.

First Nations communities in non-remote areas should have the option choose whether alternative commissioning approaches could better deliver culturally appropriate NDIS supports to meet their needs.

Learnings and experience to date from the NDIS thin market trials also indicate that NDIA needs to build their capacity and capability to roll out alternative commissioning approaches. Part of building NDIA’s capability will be to ensure a sound foundation (or ‘building blocks’) for alternative commissioning (Figure 14).

Commencing alternative commissioning pilots as soon as possible will help to understand what works and allow time to develop and strengthen partnerships with communities. An evaluation of these pilots should inform how to progress the full roll out of alternative commissioning. The evaluation should also review the extent to which integrated commissioning approaches are preferred by both First Nations and remote communities and how they can improve outcomes for participants in these communities

Over time, communities should be supported to buy and coordinate the supports for themselves. Communities would design the approach and lead the commissioning process.

Back to top