On this page

- How are price caps set in the NDIS?

- Most price caps are set based on an estimate of the ‘cost of service provision’ for the lowest-cost providers

- Price caps act more as a ‘price anchor’ than a ‘price ceiling’

- Price caps can have unintended consequences

- The NDIA does not take advantage of its buying power to get a good price, even in well-established markets

- Price caps are not well aligned across the care and support sector

- Finding 1: There are opportunities to improve NDIS pricing arrangements over the short- to medium-term

Around 80% of NDIS payments between October and December 2022 were subject to a price cap.[28]

Price controls also include billing rules as well as limits on ‘quotable supports’. ‘Quotable supports’ is where a participant is required to submit quotes to the NDIA for approval rather than using a published price cap (Figure 8).

Price caps were meant to support the scheme during the early stages of market development. The intention was to prevent any large providers from using their market power to drive up prices, while also improving efficiency and ensuring scheme sustainability.

During transition, price controls are in place to ensure that participants receive value for money in the supports that they receive. In the short to medium term, price controls are required for some disability supports because the markets for disability goods and services are not yet fully developed. The longer-term goal of the NDIA is to remove regulatory mechanisms from the markets for disability supports.

Ten years on, price caps have continued to be the primary tool used by the NDIA to steward the market and drive a measure of ‘cost efficient’ service delivery. That said, there are a few places where the NDIA is exploring different approaches to pricing (such as, by establishing a continence provider list).[29]

How are price caps set in the NDIS?

The NDIA has authority for setting price caps for NDIS supports (Figure 9).

In setting price caps, the NDIA has stated its intent has been to encourage growth in supply while driving efficiency, and ensuring participants receive value-for-money supports.[31]

A lack of independent advice and evidence around pricing decisions has added to uncertainty for providers, and can potentially discourage investment in the sector. For example, prices for some supports have been frozen over recent years (such as, for therapy supports, which have been frozen since 2019-20). While the NDIA has established a Pricing Reference Arrangements Group to provide advice to the NDIA Board[32], this alone has not been sufficient to deliver transparency and certainty for providers.

The approach used in the NDIS contrasts with price setting arrangements in aged care, which is moving toward independent price monitoring. From July 2023, the Independent Hospital and Aged Care Pricing Authority (IHACPA) will provide independent advice to government on pricing for residential aged care, residential respite care and in-home care. The Minister for Health and Aged Care will retain authority for price setting.

In 2017, the Productivity Commission noted its concern that while '… the price-setting mechanism is held within the NDIA, there is an incentive for it to be used to offset budget pressures'.[33] The Productivity Commission emphasised the need for prices to be set with market development as the primary focus.

In practice, setting prices for NDIS supports is complex. Price caps need to balance many objectives including promoting cost efficiency, stimulating innovation, encouraging the supply of quality supports, maintaining and building safeguards, and ensuring scheme sustainability.

Back to topMost price caps are set based on an estimate of the ‘cost of service provision’ for the lowest-cost providers

Each year, the NDIA undertakes an annual Financial Benchmarking Survey, where it collects information on providers’ operating costs.

The survey provides only a limited and potentially biased understanding of prices and costs. The 2021-22 NDIS Financial Benchmarking Survey had a response rate of around 15%.[34] Previous surveys were limited to providers who claimed the Temporary Transformation Payment (TTP) since responding to the survey was a requirement to receive the payment. From 2019-20, the survey has been opened to all NDIS relevant providers. However, responses continue to be dominated by TTP recipients (83% of respondents received a TTP).[35]

For supports delivered by disability support workers, price caps are informed by the survey and the estimated cost for the lowest-cost 25th percentile of providers in each of the four metrics plus a margin (Figure 10).[36] (Note, eligible providers can also apply for the TTP.)

This means, for a given price cap, fewer than one in four providers may incur costs less than the price cap.

This design of price caps was largely intended to help shape the NDIS market by rewarding the most efficient providers while the market developed and stabilised in the short term. Therefore, price caps play a significant role in controlling short-term scheme costs but can have adverse long-term consequences. Over time, competition was expected to drive provider efficiency.

The approach used by the NDIA sets the ‘efficient’ or ‘benchmark’ cost at a lower point than some other social services. For example, the ‘efficient cost’ for funding public hospitals, or the Nationally Efficient Price, is based on the average cost of an episode of care provided in public hospitals.[37]

The design of NDIS price caps was largely intended to help shape the NDIS market by rewarding the most efficient providers while the market developed and stabilised in the short term. Over time, competition was expected to drive provider efficiency.

Evidently, price caps play a significant role in controlling short-term scheme costs but can have adverse long-term consequences.

Price caps act more as a ‘price anchor’ than a ‘price ceiling’

Providers [are] always charging the full NDIS rate even though it's just a guide.

Setting an efficient or benchmark price itself can have sustainability benefits.

Getting the level of this ‘efficient’ price right is hard but vital for encouraging supply.

A price level that is too low may not incentivise providers to join the scheme and prevent participants from having access to adequate supports.[39] The NDS State of the Disability Sector Report 2022 found that almost three out of five (59%) of surveyed providers said they were worried they would not be able to provide NDIS services at current prices.[40]

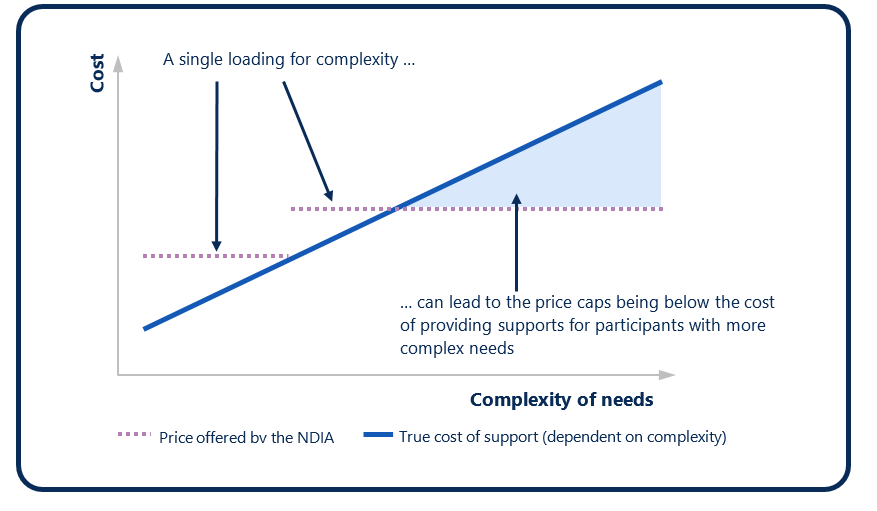

Price caps can also create unintended service gaps where they do not take into account differences in ‘market’ price at which providers are willing to supply services – such as, for participants with more complex needs.

In the NDIS, most transactions occur at the price cap. Of those supports subject to a price cap, 82% of the total value for supports between March 2022 and March 2023 were charged at or close to the price cap.[41]

Price caps appear to be acting more as a ‘price anchor’ than a ‘price ceiling’. A lack of price responsiveness from participants Section 1) may be a contributing factor. In the NDIA’s 2020-21 Financial Benchmarking Survey, over four in five providers (83%) reported always setting prices at the price cap. A small share of providers (16%) said that they ‘sometimes’ set prices below the price limit. The top reasons for doing so included: participants’ budgets having limited funds and needing to be reviewed; and providers wanting to remain competitive.

Other jurisdictions have had similar experiences of price caps anchoring prices to a fixed point that reduces price dispersion.[42]

Back to topPrice caps can have unintended consequences

The current pricing model used by the NDIS is flawed … This approach creates incentives for providers to cut costs rather than improve quality, leading to homogeneity rather than innovation and poorer outcomes for people with disabilities. In the long run, this approach is not only harmful to those who need high quality services, but also unsustainable for the NDIS itself.

The current price caps can also lead to ‘cream skimming’ where providers only take on participants who present the ‘highest profit margin’. In this way, price caps can create unintended service gaps where they do not take into account differences in the ‘market’ price at which providers are willing to supply services (Figure 11). There are reports that some participants with complex needs are having difficulty accessing supports.

The committee has heard on many occasions that the NDIS pricing framework is not working for participants with high and complex needs.. … Indeed, the committee has heard evidence that some service providers are 'cherry picking' clients and potentially leaving some of the most vulnerable NDIS participants with no access to adequate services.

Price-caps for plan- and agency-managed participants may also provide an incentive for participants to shift to self-management when they would not otherwise do so, effectively ‘side-stepping’ price caps.

On this same basis, without competitive market pressure, price caps may create a disincentive for providers to register. In its submission to the NDIS Review, the platform provider Hireup argued there is a need to '… remove the significant financial incentives that are driving up the prevalence of inexperienced independent contractors who are attracted to the sector based only on massive hourly rates, and beyond the reach of proper protections from the regulator or an employer.'[45]

Another challenge arising from price caps acting more as a price anchor is that the same corporate overheads and supervisory costs are built into the price caps irrespective of the delivery approach. Hireup recommended that NDIS pricing arrangements be '… adjusted to create differentiation between providers with different degrees of overheads due to extra costs of employment and registration.'[46] However, price differentiation that is based on ‘how’ services are delivered, rather than the underlying ‘market’ rate, is likely to limit innovation in the NDIS.

Some providers have also suggested that they are unable to invest in the capability of their workforce under current pricing arrangements and where workers can leave and set up as independent contractors or join online platforms. This exacerbates workforce retention challenges. Disability support workers and unions have also raised issues with workers not necessarily being paid wages that reflect the complexity or difficulty of the work.[47]

These examples of the unintended consequences of price caps highlight the need for more detailed information on the ‘true’ cost of service delivery. For example, governments do not visibility on the full operating and overhead costs of sole traders and platform workers.

Back to topThe NDIA does not take advantage of its buying power to get a good price, even in well-established markets

Price caps for therapy supports are informed by prices in the large and well-established private market for therapy supports. For therapy supports, the NDIA sets price caps with reference to available information on the top 75th percentile of private market prices.

As part of the 2021-22 Annual Pricing Review, the NDIA collected some data on the advertised rates of therapy supports delivered in the private market. This suggested the average hourly cost of therapy supports was $172 in the private market[48], compared with the NDIS price limit of $194 per hour for most therapy supports in non-remote areas.[49]

The NDIA is a reasonably large purchaser of therapy supports in what is a well-established market. In 2021-22, over 530,000 participants (98%) had therapy supports in their plans.[50] In the same year, agency- and plan-managed participants spent over $2.6 billion on therapy supports. In the same year, agency- and plan-managed participants spent over $2.6 billion on therapy supports.[51]

Despite this, participants and disability representative and carer organisations report that participants pay more for therapy supports than non-NDIS participants, with some calling this ‘price gouging’.

When we go to therapies we pay the maximum price of the pricing arrangements when I could go in under my private health and not pay anywhere near the same costs.

I try to use mainstream services and products rather than go to disability specific market due to the ridiculous prices charged by providers. As has been stated time and again, an able bodied person can go to an allied health professional and be charged $90, but I go for the same service and because I am NDIS funded I get charged more than $200 … Not only is it discriminatory but also costs the government more dollars, and the person with disability gets less support.

Because the NDIS Pricing Arrangements and Price Limits covering particular therapy supports far exceed the fees charged by these providers to non-Participants, there is an inherent incentive for these providers to charge more than they might otherwise if the NDIS will write the cheque..

Similar concerns have been raised for assistive technology.

Too many people see it as easy money, at the expense of the disabled community. Legislating to prevent companies charging a private individual $2,000 for a wheelchair and the NDIS $8,000 for the same product..

‘Price gouging’ or setting excessively inflated prices are not on their own illegal.[56] However, under Australian competition laws, businesses must not engage in anti-competitive behaviour that misleads consumers about what they’ll be charged or why, and must not collude with their competitors in setting prices.

That said, there is a high prevalence of providers charging at the price cap. In 2021-22, just under three in four (72%) therapy sessions delivered to agency- and plan-managed participants were charged at or close to the price cap.[57] The NDIA does not systematically collect data on therapy supports delivered to self-managed participants.

There may be valid reasons why prices are higher for some participants.

Providers may face additional regulatory and administrative costs when delivering services to NDIS participants. For example, while the range of audit costs vary according to provider size and scope, registered NDIS providers face a median cost of $935 for verification audits, which must be conducted every three years.[58] Registered NDIS providers who deliver more complex supports face a median cost of around $3,000 for certification audits. These audits must be conducted every three years, with mid-term certification at the 18-month mark.[59]

Price differences may reflect differences in participant complexity or delivery method and, in these cases, may be appropriate if they improve participant outcomes.

Price differences may reflect differences in participant complexity or delivery method and, in these cases, may be appropriate if they improve participant outcomes.

My planner complained about the charge our physio charges us, but it is in line with NDIS price guidelines. When I explained this to my planner, she advised that was only a ceiling and no one should be charging that much. If you are going to put high prices in your price guidelines, you have to expect to be charged those prices..

Re-thinking how participants and providers are incentivised through the scheme settings will therefore be critical in designing the long-term price settings (Section 5).

Back to topPrice caps are not well aligned across the care and support sector

Price caps are also used in the broader care and support sector, including in Commonwealth-funded aged care and veterans’ care sectors.

However, there is no coordinated approach to setting prices across these sectors, and prices vary across programs. These differences can create a situation where the Government is effectively ‘competing’ with itself on prices across the care and support sector.

There could be benefit in considering whether prices could be more closely aligned across the care and support sector, drawing on governments ‘buying power’. This could support scheme sustainability, more efficient use of government funding and ensure that providers and workers are not deterred from offering services to different sectors, on the basis of different pricing.

Back to top